Corpus: Rectum

from Latin: rectus - straight

1. Definition

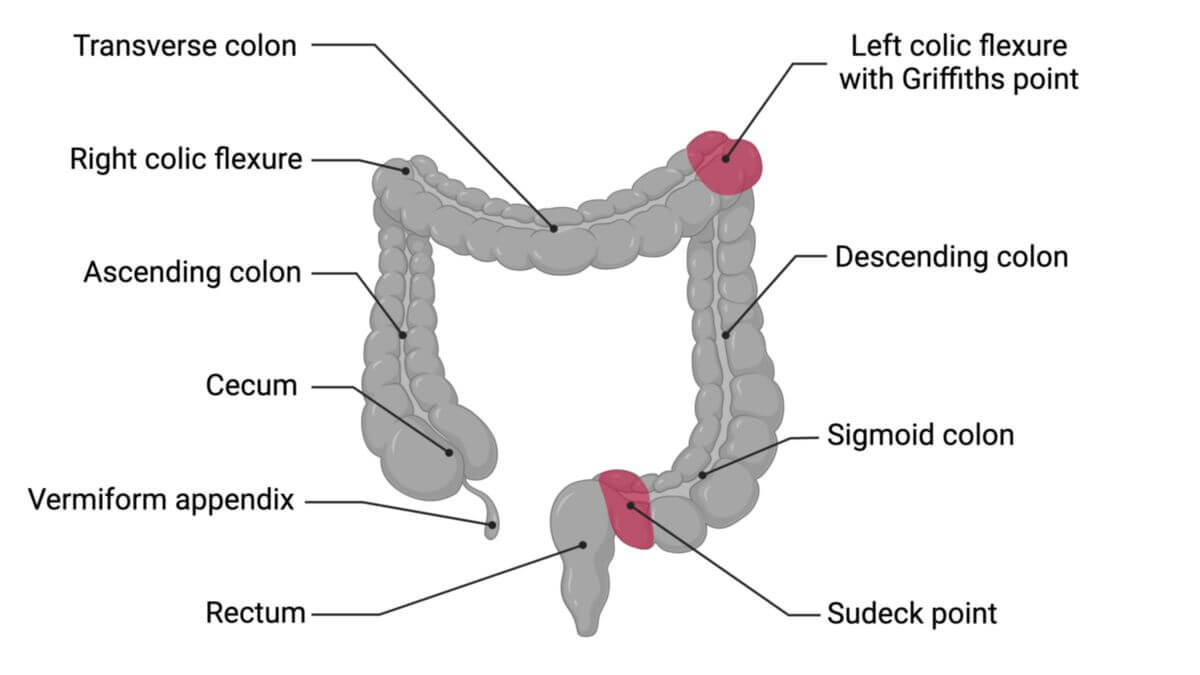

The rectum is the section of the large intestine that connects the sigmoid colon to the anus.

2. Anatomy

The rectum is approximately 12 to 15 cm long in adults and is located in the lesser pelvis. It begins at the level of the sacrum and curves dorsally (sacral flexure) and ventrally (perineal flexure) as it extends toward the anus. The rectum transitions into the anal canal in the area of the continence organ. Most of the rectum lies either behind or outside the peritoneum (retroperitoneal or extraperitoneal; referred to as "fixed rectum"). A small upper portion, however, can sometimes lie within the peritoneal cavity (intraperitoneal; referred to as "mobile rectum").

Inside the rectum, there are numerous transverse folds known as rectal folds (plicae transversales recti). The most prominent fold, called the Kohlrausch fold, is located approximately 6–8 cm from the anus and marks the beginning of the rectal ampulla. The ampulla extends caudally and transitions into the anal canal at the anorectal junction.

In males, the fold between the rectum and the urinary bladder is known as the rectovesical pouch. In females, the uterus creates two distinct folds: the rectouterine pouch (Douglas space) and the vesicouterine pouch.

Several interconnected spaces surround the rectum, including the pararectal and retrorectal spaces.

2.1. Morphological peculiarities

At the junction between the sigmoid colon and the rectum, the rectum loses the typical features of the colon:

- The haustra (sacculations of the colon) with their semilunar folds disappear.

- The longitudinal muscle bands (taeniae)

- Fat-filled peritoneal appendages (epiploic appendages)

Instead of semilunar folds, the rectal mucosa contains transverse rectal folds (plicae transversae recti). The longitudinal muscle layer of the rectum is completely continuous, unlike the segmented bands (taeniae) of the colon.

From an embryological perspective, the rectum above the anorectal line develops from the endodermal hindgut along with the rest of the large intestine. The anal canal, however, originates from the ectodermal anal pit.

2.2. Arterial supply

The rectum receives its blood supply primarily from three arteries:

- The superior rectal artery (from the inferior mesenteric artery)

- The middle rectal artery (from the internal iliac artery)

- The inferior rectal artery (from the internal pudendal artery)

2.3. Venous supply

The rectal veins correspond to the arteries and drain into different venous systems:

- The superior rectal vein drains into the portal vein.

- The middle and inferior rectal veins drain into the systemic circulation via the internal iliac vein and ultimately into the inferior vena cava.

Medications administered rectally as suppositories, largely bypass the liver due to these venous drainage patterns, allowing direct entry into systemic circulation.

2.4. Innervation

The rectum receives autonomic innervation through the superior and middle rectal nerve plexuses, which are connected to the inferior mesenteric plexus and the inferior hypogastric plexus.

3. Histology

Like the other sections ot the intestine, the rectal wall consists of five distinct layers, organized from the inside out as follows:

- Mucosa

- Epithelium: A single layer of tall columnar cells with goblet cells for mucus production.

- Lamina propria: Contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and lymph follicles.

- Muscularis mucosae: A thin layer of smooth muscle beneath the mucosa.

- Submucosa: Connective tissue with a network of nerves (submucosal plexus).

- Muscularis propria: Contains an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer of smooth muscle.

- Subserosa (in the distal area adventitia): A connective tissue layer.

- Serosa: Found only in the upper portion of the rectum where it transitions to the sigmoid colon.

4. Function

The rectum serves as a reservoir for feces. It works in conjunction with the muscles of the continence organ to store stool and facilitate voluntary, controlled defecation. Stretching of the rectal wall triggers a reflexive increase in sphincter tone, ensuring continence until defecation occurs.

5. Clinical relevance

Inflammation of the rectal wall is called proctitis. Other common rectal conditions include:

- Rectal cancer

- Rectal polyps

- Rectal foreign bodies

- Perirectal abscesses

- Hemorrhoids

- Proctalgia fugax (episodic rectal pain)