Corpus: Knee joint

1. Definition

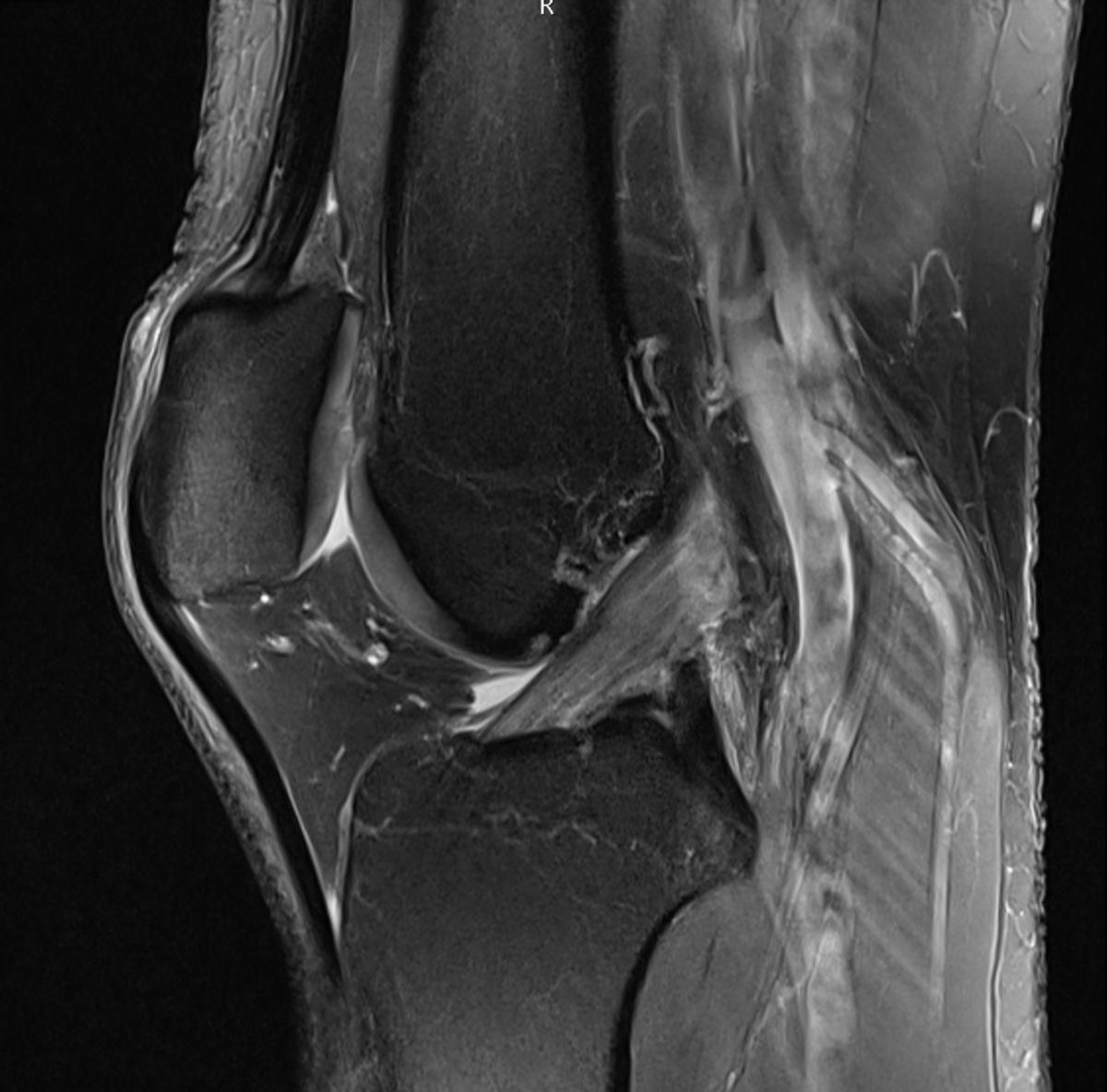

2. Anatomy

2.1. Structure of the joint

The knee joint consists of two parts that share a common joint capsule or cavity. The connection between the femur and tibia is called the femorotibial joint. The joint between the femur and kneecap is known as the femoropatellar joint.

The femorotibial joint is a bicondylar joint, where the rounded femoral condyles connect with the slightly concave, oval-shaped upper surfaces of the tibial condyles. Additionally, the femur has an articular surface (patellar surface) for the cartilage-covered articular surface of the patella.

2.2. Bones

2.2.1. Femur

The femoral condyles in the knee joint have a greater curve (smaller radius of curvature) at the back than at the front. The line that connects the centers of these different curvatures is called the involute.

Tibia

The tibia is wider at the top, forming the tibial plateau, which includes the medial and lateral condyles. Each condyle has an articular surface (superior articular surface) on its upper side. Between the two condyles lie the anterior and posterior intercondylar areas, along with the intercondylar eminence, which includes the medial and lateral intercondylar tubercles. The head of the tibia is tilted backward by about 3 to 7 degrees. In newborns, the tilt can be as much as 30 degrees.

Patella

The patella, a sesamoid bone, is located within the tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle. On the back of the patella is its cartilage-covered articular surface, which glides along the patellar groove on the femur. This surface is divided into a larger lateral facet and a smaller medial facet by the longitudinal ridge.

Articular cartilage

The knee joint has the largest articular surface and the thickest cartilage in the body. The joint surface covers about 100 cm² (excluding the menisci), with the femur contributing approximately 61 %. The articular surface of the patella, which is up to 7 mm thick, is the thickest part of the knee. In women, the joint surface is about 30 % smaller compared to men, but only 10 % thinner.

2.3. Menisci

The fibrocartilaginous menisci, including the medial (inner) and lateral (outer) menisci, are located between the femur condyles and the tibial plateau. Viewed from above, the menisci appear C-shaped and have a wedge-shaped cross-section, with the wider side fused to the joint capsule. The underside of the menisci is flat and rests on the articular surfaces of the tibial plateau, while the upper side is slightly concave, conforming to the shape of the femoral condyles. The free ends of the menisci (anterior and posterior horns) are attached to the intercondylar area of the tibia. The lateral meniscus is more circular, with its anterior and posterior horns attaching near the lateral intercondylar tubercle.

The medial meniscus is more sickle-shaped, so its anterior and posterior horns are positioned farther apart. The anterior horn is anchored in the anterior intercondylar area by the anterior meniscotibial ligament, while the posterior horn attaches at the back of the medial intercondylar tubercle through the posterior meniscotibial ligament.

The medial meniscus is fused to the posterior part of the medial collateral ligament, reducing its mobility during knee flexion and extension and making it more prone to injury. The lateral meniscus, however, is not fused to the extracapsular collateral ligament, allowing greater mobility. At the front, both menisci are connected by the transverse geniculate ligament.

In 50 to 70 % of cases, additional ligaments are found between the lateral meniscus and the medial femoral condyle:

- The posterior meniscofemoral ligament (Wrisberg ligament) runs behind the posterior cruciate ligament.

- The anterior meniscofemoral ligament (Humphry ligament) runs in front of the posterior cruciate ligament.

The menisci divide the femorotibial joint into two compartments: the meniscofemoral joint and the meniscotibial joint. Their functions include increasing the contact surface between the tibia and femur, compensating for the uneven surfaces of the condyles, and stabilizing the joint. In full knee extension, the menisci are pushed to the sides, while in deep knee flexion, they are passively displaced backward, especially the lateral meniscus.

2.4. Ligaments

The knee joint is secured by complex ligaments.

2.4.1. Collateral ligaments

The collateral ligaments provide stability to the knee joint against varus (inward) and valgus (outward) stress. These include:

- Medial collateral ligament (MCL): This ligament connects the medial femoral epicondyle to the medial and dorsomedial surface of the tibial plateau. The posterior part is shorter than the anterior part and is firmly attached to both the joint capsule and the medial meniscus.

- Lateral collateral ligament (LCL): This is a round, cord-like ligament that runs from the lateral femoral epicondyle to the head of the fibula.

Unlike the medial collateral ligament, the lateral collateral ligament is not attached to the joint capsule or the lateral meniscus. The tendon of the popliteal muscle passes through the gap between the lateral collateral ligament and the joint capsule at the top, while fibers from the biceps femoris tendon pass through at the bottom.

The collateral ligaments are tight during knee extension and loosen during flexion. An exception is the posterior part of the medial collateral ligament, which limits the movement of the medial condyle during flexion. This causes the axis of rotation to shift slightly toward the medial side.

Because the collateral ligaments are tight during extension, they primarily prevent excessive abduction, adduction, and internal or external rotation. These movements become possible to a limited degree when the knee is flexed.

2.4.2. Cruciate ligaments

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is attached to the inner surface of the outer femoral condyle and extends towards the front of the tibia's intercondylar area. It runs within the joint cavity from the back, top, and outer side to the front, bottom, and inner side.

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is attached to the front inner surface of the inner femoral condyle and extends diagonally backward to the back of the tibia's intercondylar area. It runs from the front, top, and inner side to the back, bottom, and outer side.

Both cruciate ligaments are tight in almost all positions, helping to stabilize the knee joint. When the knee is bent, the ACL primarily prevents the femur from sliding backward out of place. When the knee is straightened, the front part of the ACL and the back part of the PCL tighten. During internal rotation, the cruciate ligaments cross over each other, and during external rotation, they separate. Additionally, these ligaments contain mechanoreceptors that help control movement and trigger protective reflexes.

During embryonal development, the cruciate ligaments enter the intercondylar fossa from the back and bring along the synovial membrane but not the fibrous capsule of the joint. Therefore, they are located within the joint capsule (intracapsular) but not in the synovial cavity. This is called a "retro-" or "extrasynovial" location.

2.4.3. Other ligaments

In addition to the collateral and cruciate ligaments and the ligaments associated with the menisci, there are other important ligaments in the knee joint:

- Patellar ligament: This is a continuation of the quadriceps femoris muscle tendon and helps secure the knee joint from the front.

- Patellar retinaculum: This structure also supports the knee joint anteriorly.

- Iliotibial tract: This thick band of connective tissue on the outer side of the thigh contributes to knee stability.

- Popliteal ligaments: These include the oblique popliteal, arcuate popliteal, and popliteofibular ligaments, which help stabilize the knee from the back and sides.

Some orthopedic surgeons suggest the presence of an additional ligament called the anterolateral ligament (ALL) in the knee joint. However, its existence remains a topic of debate.

2.5. Joint capsule

The knee joint is encased in a wide joint capsule that covers all the articular surfaces, including the patella. The capsule has two layers:

- Fibrous membrane: This outer layer provides stability through its fibrous structure.

- Synovial membrane: This inner layer lines the inside of the knee joint and produces synovial fluid.

In a horizontal section, the space within these two membranes has a horseshoe shape because the posterior cruciate ligament lies outside the synovial membrane.

The joint capsule is most stable on the dorsal side of the knee. This area features intersecting fiber tracts, some of which extend to the head of the fibula. Notable ligaments here include the popliteal oblique ligament and the popliteal arcuate ligament. The popliteal oblique ligament, which is an extension of the semimembranosus muscle tendon, runs from the medial and lower part of the knee to the lateral and upper part. The popliteal arcuate ligament extends laterally toward the fibular head. The posterior capsule is also reinforced by the tendons of the two heads of the gastrocnemius muscle.

Distally, the capsule attaches to the edges of the tibial condyles and merges with both menisci. On the front (ventral) side, it is securely connected to the patellar ligament.

Additionally, the joint cavity contains folds of synovial membrane which divide the joint space. These include the alar, suprapatellar, medipatellar and infrapatellar folds.

The joint capsule is least taut when the knee is flexed at 20 to 30 degrees. This is the typical position in the case of joint swelling (effusion).

2.6. Infrapatellar fat pad

The infrapatellar fat pad, also called Hoffa's fat pad, is a pyramid-shaped structure located between the lower edge of the patella and the front edge of the tibia and the patellar ligament. It acts as a cushion for the synovial membrane and is positioned between the fibrous membrane and the synovial membrane.

Bursae

The knee joint is surrounded by several bursae, which are fluid-filled sacs that reduce friction between tissues. Some bursae communicate with the joint capsule, while others do not.

- Suprapatellar bursa: Located above the patella, between the femur and the quadriceps tendon. It communicates with the joint cavity and is also known as the suprapatellar recess.

- Prepatellar bursae: Found in front of the kneecap, between the patella and the overlying tissues (tendon, fascia, skin). These bursae do not connect to the joint cavity.

- Infrapatellar bursa: Located below the patella, between the patellar ligament and the tibia.

Other bursae in the knee area include the anserine bursa, popliteal bursa, semimembanosus bursa, medial and lateral bursa of gastrocnemius muscle, inferio bursa of biceps femoris muscle and subcutaneous bursa of the tibial tuberositas.

2.7. Arterial supply

The arterial supply to the knee joint is provided by a large number of different arteries, which anastomose with each other and thus form a dense collateral network. These include:

- Descending genicular artery

- Middle genicular artery

- Superior lateral genicular artery

- Superior medial genicular artery

- Inferior lateral genicular artery

- Inferior medial genicular artery

2.8. Topography

Ventral to the knee joint, or on the extensor side, is the anterior aspect of the knee. On the flexor side, this region is known as the posterior aspect of the knee, where the popliteal fossa is located. This fossa is an important area where several critical structures pass through, including the popliteal artery and the tibial nerve. Additionally, there are several lymph nodes in this region, called the popliteal lymph nodes.

3. Biomechanics

3.1. Femorotibial joint

Functionally, the femorotibial joint is a trochoginglymus, i.e. a combination of:

- Hinge joint (ginginglymus): Hinge movement around transverse axis.

- Rotational joint (wheel joint): Rotational movement around longitudinal axis.

It enables extension and flexion movements as well as internal and external rotation. Abduction and adduction are only possible by a few degrees.

3.1.1. Extension and flexion

Active flexion is possible up to 125° with the hip joint extended and up to 140° with the hip joint flexed. This increase can be explained by the pre-stretching or lengthening of the ischiocrural musculature, which overcomes the active insufficiency. Passive flexion is limited to 160° by pressing the dorsal thigh and lower leg muscles together (mass inhibition).

Extension can be achieved up to 0°; passive hyperextension of 5 to 10° can be achieved.

The movement is a combined rolling-twisting movement: In the initial phase of flexion (up to approx. 25°), the femoral condyles roll dorsally, comparable to a rocking chair. With greater flexion, the condyles rotate on the spot with slight sliding movements. At maximum flexion, the contact surface between the femur and tibia is located at the posterior edge of the tibia. During flexion, the menisci move dorsally, with the outer meniscus travelling a greater distance due to its greater mobility. During extension, the menisci move back ventrally, and in the neutral position they are pushed to the side.

3.1.2. External rotation and internal rotation

Rotation of the tibia against the femur is only possible in the flexed joint if the collateral ligaments and the joint capsule are relaxed. In the flexed joint, the lower leg can be rotated outwards to a greater extent (approx. 30°), as internal rotation is inhibited by the coiling cruciate ligaments (up to 10°). During external rotation, the lateral meniscus moves forwards, while the medial meniscus moves backwards. These movements are reversed during internal rotation.

During the final phase of extension (from approx. 10°), the tibia is inevitably externally rotated by 5 to 10° (final rotation): This is caused by the tension of the anterior cruciate ligament and the differences in the shape of the femoral condyles. During the final rotation, the collateral ligaments reach a high state of tension so that the knee joint is stabilised. Before flexion, the tibia must be internally rotated again by 5 to 10° (flexion stabilisation).

3.2. Femoropatellar joint

In the extended knee joint, the patella lies on the suprapatellar bursa and only touches the joint surface of the femur with its lower edge. With increasing flexion, the patella enters the gliding path between the femoral condyles and covers a total distance of 5 to 7 cm. During flexion, the contact surfaces move from the distal to the proximal patellar pole. During flexion at 120°, the patella moves between the condyles; at 140°, the patella articulates with the odd facet.

The vastus medialis muscle is crucial for guiding the patella, as the quadriceps femoris muscle and the patellar ligament do not form a line but have an inwardly open angle. The lateral tensile component of the quadriceps muscle leads to a laterally emphasised stress on the joint surface.

In deep flexion, the femoropatellar joint is subjected to forces that can exceed six times the body weight. They are partially transmitted by the quadriceps tendon, but the articular cartilage is nevertheless exposed to considerable forces. For this reason, injuries and signs of degeneration of the retropatellar cartilage (chondromalacia patellae) are among the most common types of cartilage damage.

4. Clinic

4.1. Diseases

The knee is primarily affected by degenerative diseases or injuries (knee joint trauma). In addition to gonarthrosis, damage to the ligamentous apparatus (e.g. cruciate ligament rupture, collateral ligament rupture) or the menisci (meniscus rupture) are the main causes, for example as part of an unhappy triad. If the ligaments tear out at the bone level, this is referred to as avulsion fractures of the knee.

Inflammation of the knee joint (gonarthritis) can also occur, for example in the context of rheumatoid diseases.

4.2. Diagnostics

The diagnosis begins with a medical history and a clinical examination of the knee joint. Typical leading symptoms are knee pain (gonalgia), limited resilience and swelling of the knee. Depending on the suspected diagnosis, imaging (sonography, X-ray, CT, MRI) and endoscopic procedures (knee joint arthroscopy) are used.

As part of the clinical examination, the following signs can be checked or tests carried out:

- Steinmann I sign

- Steinmann II sign

- Böhler sign

- Payr sign

- Drawer test

- Apley Grinding Test

see also: Knee joint examination

4.3. Joint replacement

Like the hip joint, the knee joint can also be replaced by total knee arthroplasty, so-called knee joint endoprostheses.