Corpus: Pancreas

from ancient Greek: pánkreas, πᾶν ("pán") - "everything", κρέας ("kréas") - "meat"

1. Definition

The pancreas is a glandular organ located transversely in the upper abdomen, responsible for producing digestive enzymes and hormones.

2. Anatomy

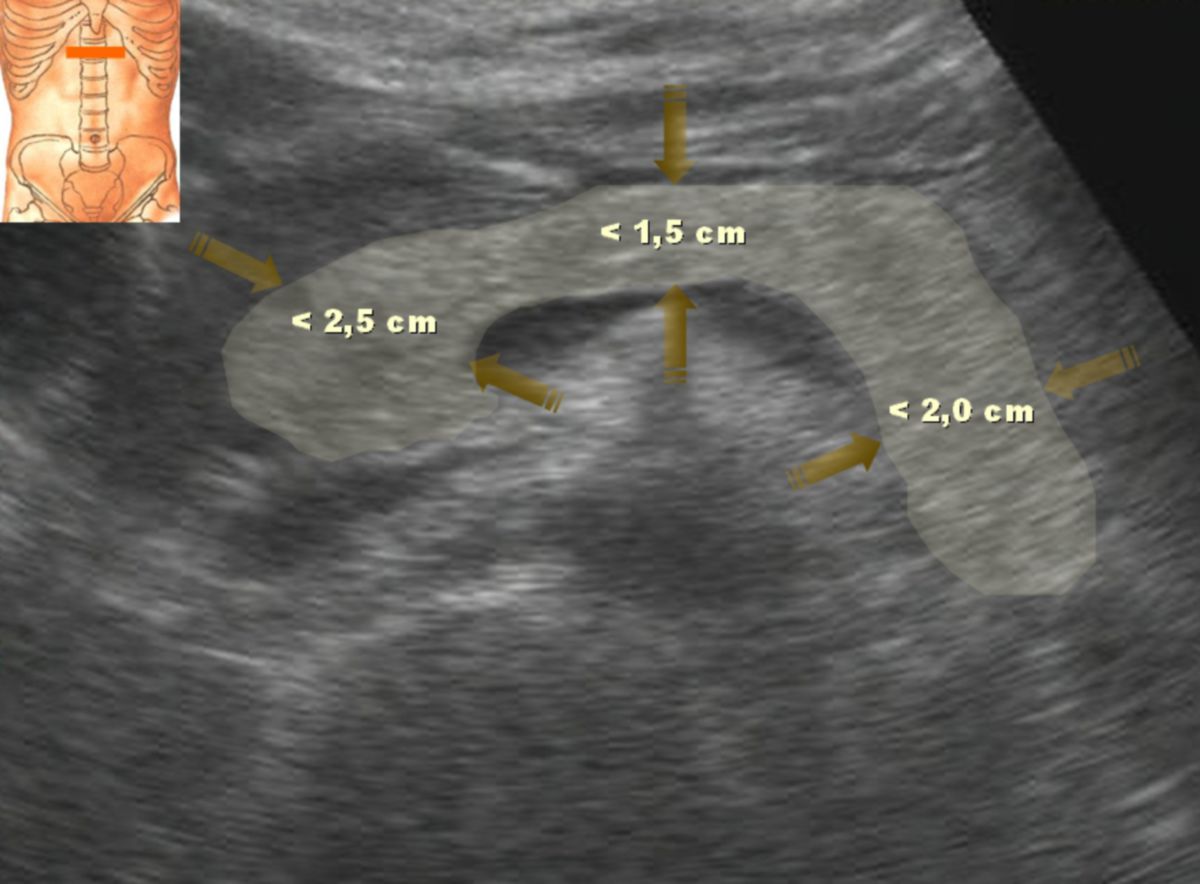

2.1. Dimensions

The pancreas is a wedge-shaped organ about 14 to 18 cm in length, divided into irregular lobules. The organ weight varies between individuals, ranging from 60 to 100 g, though other sources suggest between 40 and 120 g.[1]

2.2. Structure

The pancreas lies secondarily retroperitoneal, positioned between the stomach and major abdominal vessels (aorta and inferior vena cava) at the level of the 2nd lumbar vertebra. It is closely related to the duodenum, which encircles the pancreatic head. The pancreas is divided into three main sections:

- Head: The thickest part, located to the right of the spine within the duodenal curve. It has a hook-like projection called the uncinate process that surrounds the superior mesenteric artery. This region, called the pancreatic notch, connects the dorsal side to the front of the pancreas.

- Body: The elongated, horizontal part of the pancreas lies at the level of L1-L2. Its posterior surface is fused to the dorsal abdominal wall, while its anterior surface is covered by peritoneum, forming the posterior wall of the omental bursa. The portion that extends over the abdominal aorta into the omental bursa is known as the omental tuberosity.

- Tail: The narrow end of the pancreas, extending toward the spleen and positioned in the splenorenal ligament.

Due to its role as a digestive gland, the pancreas has an excretory duct called the pancreatic duct, which opens into the duodenum along with the common bile duct from the liver and gallbladder. These ducts empty near or at a small, wart-like elevation called the major duodenal papilla. The pancreatic duct is about 2 mm wide and receives short, vertical inflows from the pancreatic lobules. Occasionally, there is an additional pancreatic duct, known as the accessory pancreatic duct, which opens at the minor duodenal papilla (see section "Embryology").

2.3. Arterial supply

The pancreas receives its arterial blood supply from the following sources:

- The superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, originating from the gastroduodenal artery.

- The inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, arising from the superior mesenteric artery.

- The splenic artery, a branch of the celiac trunk, with its branches:

- Dorsal pancreatic artery

- Inferior pancreatic artery, which is a continuation of the dorsal pancreatic artery

- Great pancreatic artery

- Caudal pancreatic artery

The two pancreaticoduodenal arteries form an anastomosis in the pancreas, creating collateral circulation between the celiac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery.

Both the splenic artery and the inferior pancreatic artery run horizontally along the dorsal side of the pancreas toward the tail and splenic hilum. Along this path, they form vertical anastomoses, with the splenic artery running along the upper edge and the inferior pancreatic artery running along the lower edge of the pancreas.

2.4. Venous outflow

The venous drainage of the pancreas occurs through the pancreaticoduodenal veins, which primarily drain into the superior mesenteric vein. Additionally, smaller veins on the dorsal side of the pancreas, known as pancreatic veins, drain into the splenic vein.

2.5. Nervous supply

Like other abdominal organs, the pancreas is innervated by the autonomic nervous system. Parasympathetic innervation is provided by fibers from the vagus nerve, while sympathetic innervation comes from fibers originating in the celiac ganglion. The pancreas contains receptors that modulate its secretory activity. α2-adrenoceptors inhibit the secretion of β-cells, which produce insulin, and δ-cells, which produce somatostatin, while increasing the secretion of α-cells, which produce glucagon. In contrast, β2-adrenoceptors increase the secretion of both β-cells and δ-cells.

3. Histology

The pancreas has both exocrine and endocrine functions, and these roles are distinctly represented in the tissue structure of the gland. The exocrine portion is responsible for producing digestive enzymes, while the endocrine portion regulates blood sugar and other metabolic functions through the secretion of hormones. This dual function is mirrored in the specific cellular arrangement and organization of the pancreatic tissue.

3.1. Exocrine pancreas

The exocrine pancreas makes up approximately 95 to 98 % of the tissue volume. It consists of densely packed, purely serous tubuloacinar glands that are organized into lobes and lobules. The glandular end units, known as pancreatic acini, are composed of pyramid-shaped epithelial cells called acinus cells. These cells have a broad base and a narrow apex and are arranged in a single layer around a small central lumen. Secretions from the acini are collected into a central duct segment, where specialized centroacinar cells partially protrude into the acinar lumen. These secretions then pass through intralobular and interlobular ducts lined with cylindrical epithelium before ultimately draining into the pancreatic duct.

The secretory function of acinar cells is evidenced by the large amounts of rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) and numerous Golgi apparatuses present within the cells. In the cytoplasm of the apical cell pole, zymogen granules containing inactive proenzymes are stored. These proenzymes are released by exocytosis and activated in the extracellular space. The basal pole of the acinar cells, which contains abundant RER, reacts basophilically, reflecting its high level of protein synthesis.

3.2. Endocrine pancreas

The much smaller endocrine part of the pancreas accounts for about 2 to 5 % of the tissue volume. This portion consists of approximately 1 to 2 million round cell clusters known as the pancreatic islets or islets of Langerhans, which are scattered throughout the exocrine tissue. Each islet comprises several thousand large, polygonal cells, distinguishable from the surrounding exocrine tissue due to their lighter staining properties. There are up to six distinct cell types within the islets, each producing various metabolically relevant hormones.

The islet cells are interconnected by desmosomes and gap junctions, forming strands of cells that are closely associated with fenestrated capillary endothelium, allowing for the efficient release of hormones directly into the bloodstream.

The pancreatic islets are separated from the surrounding exocrine tissue by a thin layer of reticular connective tissue. The highest density of islets is found in the body and tail of the pancreas.

4. Embryology

The pancreas develops from two initially separate structures, both of which originate from the endoderm at the level of the duodenum. The dorsal pancreas forms first on the posterior side of the duodenum and grows into the dorsal mesoduodenum. Shortly after, the ventral pancreas develops from the choledochal duct anlage, located beneath the liver. As the stomach undergoes rotation during development, the ventral pancreas shifts dorsally around the duodenum and fuses with the dorsal pancreas. The duct systems of the two portions typically merge during this process. However, in some cases, the excretory duct of the dorsal pancreas remains independent as a accessory pancreatic duct, which opens separately into the duodenum at the minor duodenal papilla.

The islets of Langerhans do not arise from a distinct embryonic structure; instead, they develop from epithelial outgrowths of the exocrine pancreas. These cells lose their connection to the ductal system and become separated from the exocrine portion by vascularized connective tissue. Through the activation of specific transcription factors, including neurogenin3 and Rfx6, these cells differentiate into various endocrine cell types without a discernible distribution pattern.

5. Function

5.1. Exocrine function

The pancreas is the most crucial digestive gland in humans, secreting a variety of digestive enzymes and proenzymes (inactive enzyme precursors). Additionally, centroacinar cells in the excretory ducts produce bicarbonate, which plays a key role in neutralizing stomach acid in the duodenum. The amount and composition of pancreatic secretions depend on the type of food ingested. In humans, up to 1.5 liters of pancreatic secretion can be produced daily, containing a variety of enzymes, including:

- Enzymes involved in protein digestion (proteases, peptidases)

- Endopeptidases

- Trypsinogen

- Chymotrypsinogen

- Elastase (proelastase)

- Exopeptidases

- Carboxypeptidases (procarboxypeptidases)

- Aminopeptidases (proaminopeptidases)

- Endopeptidases

- Enzymes for carbohydrate digestion

- Alpha-amylase

- Enzymes for nucleic acid digestion

- Ribonucleases, deoxyribonucleases

- Enzymes for fat digestion (lipases)

- Pancreatic lipase with procolipase

- Pancreatic esterase

- Lysophospholipase

- Cholesterol esterase

- Phospholipase A

- Bile salt-activated lipase (BAL)

To prevent self-digestion of the pancreatic tissue, several of these enzymes, such as proteases, colipase, and phospholipase A, are produced in their inactive forms. They are only activated once they reach the duodenum.

5.2. Endocrine function

In addition to its exocrine function, the pancreas has an endocrine component that releases hormones directly into the bloodstream. The islets of Langerhans, which are scattered throughout the pancreas, collectively function as the endocrine pancreas. Different cell types within the islets are responsible for producing specific hormones, and they are categorized as follows based on the hormone they produce:

| Cell type | Hormone produced | Proportion of human islet cells |

|---|---|---|

| α-cells | glucagon | 15–20 % |

| β-cells | insulin | 60–80 % |

| δ-cells | somatostatin | 5–15 % |

| PP cells | pancreatic polypeptide | 1–2 % |

| ε-cells | ghrelin | approx. 1 % |

| EC cells | serotonin | < 1 % |

5.3. Other functions

The pancreatic acini contain pancreatic stellate cells, which are morphologically and functionally similar to the hepatic Ito cells found in the liver. These cells are capable of storing lipids and vitamin A. When stimulated, typically in response to tissue injury, pancreatic stellate cells transform into myofibroblasts. In this activated state, they contribute to the production of connective tissue, playing a critical role in tissue repair and, in pathological conditions, fibrosis.[2]

6. Clinic

6.1. Diseases

Diseases of the pancreas include:

- Pancreatitis

- Pancreatic tumors (e.g., pancreatic carcinoma)

- Malformations of the ductal system

- Pancreatic pseudocysts

- Shwachman-Diamond syndrome

- Malformations of the entire organ,

- Annular pancreas

- Pancreas divisum

Because the pancreatic duct and common bile duct frequently join at the major duodenal papilla, diseases of the pancreas can lead to liver dysfunction, and vice versa. For example, cholangiolithiasis (gallstones obstructing the common bile duct) can cause pancreatitis by blocking pancreatic drainage. Conversely, tumors of the pancreatic head can obstruct the common bile duct, leading to impaired bile flow and resulting in post-hepatic jaundice.

Pathologies arising from the endocrine pancreas include pancreoprive diabetes mellitus and hormone-producing tumors such as insulinomas (which produce insulin) and glucagonomas (which produce glucagon).

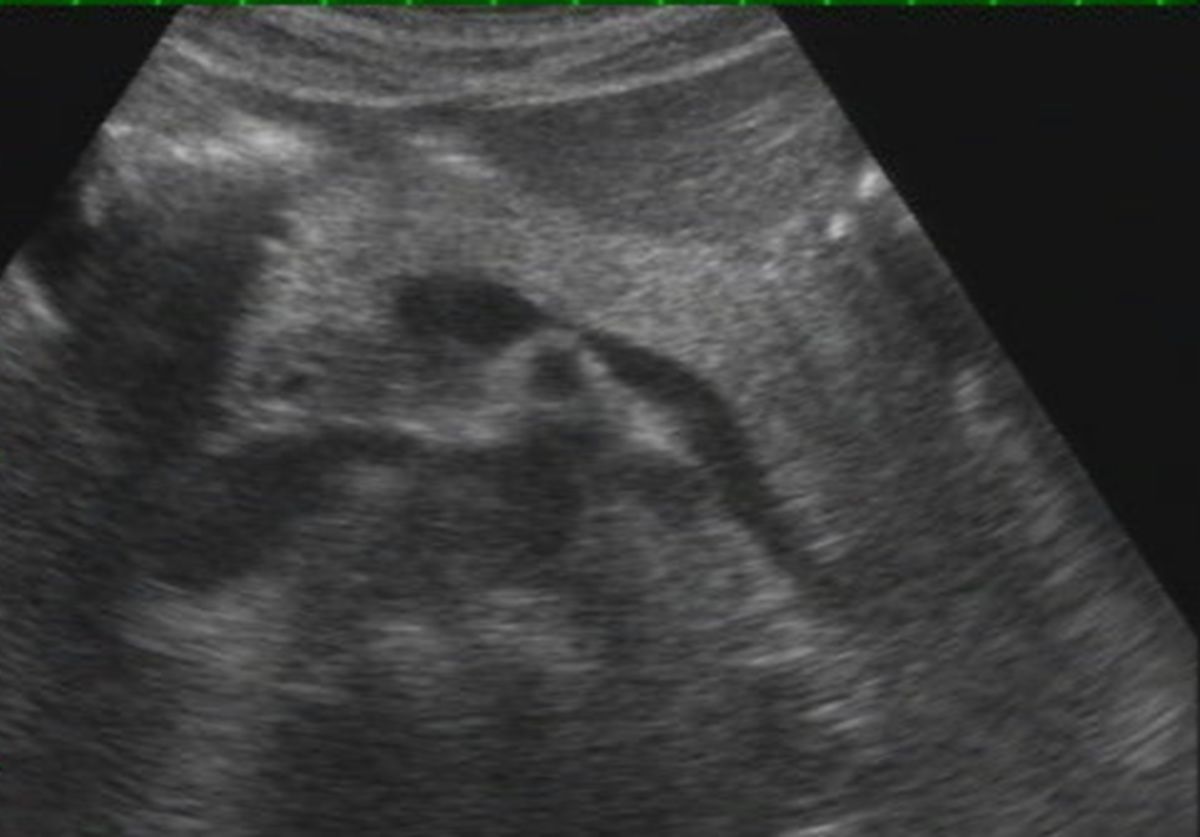

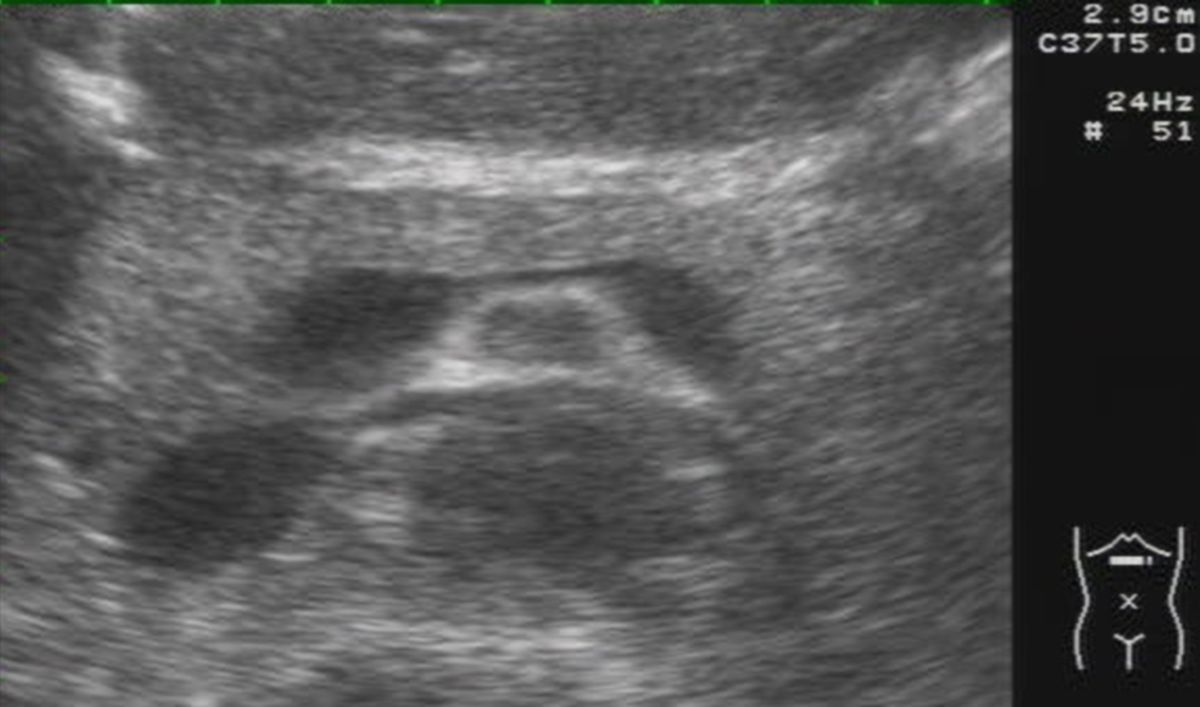

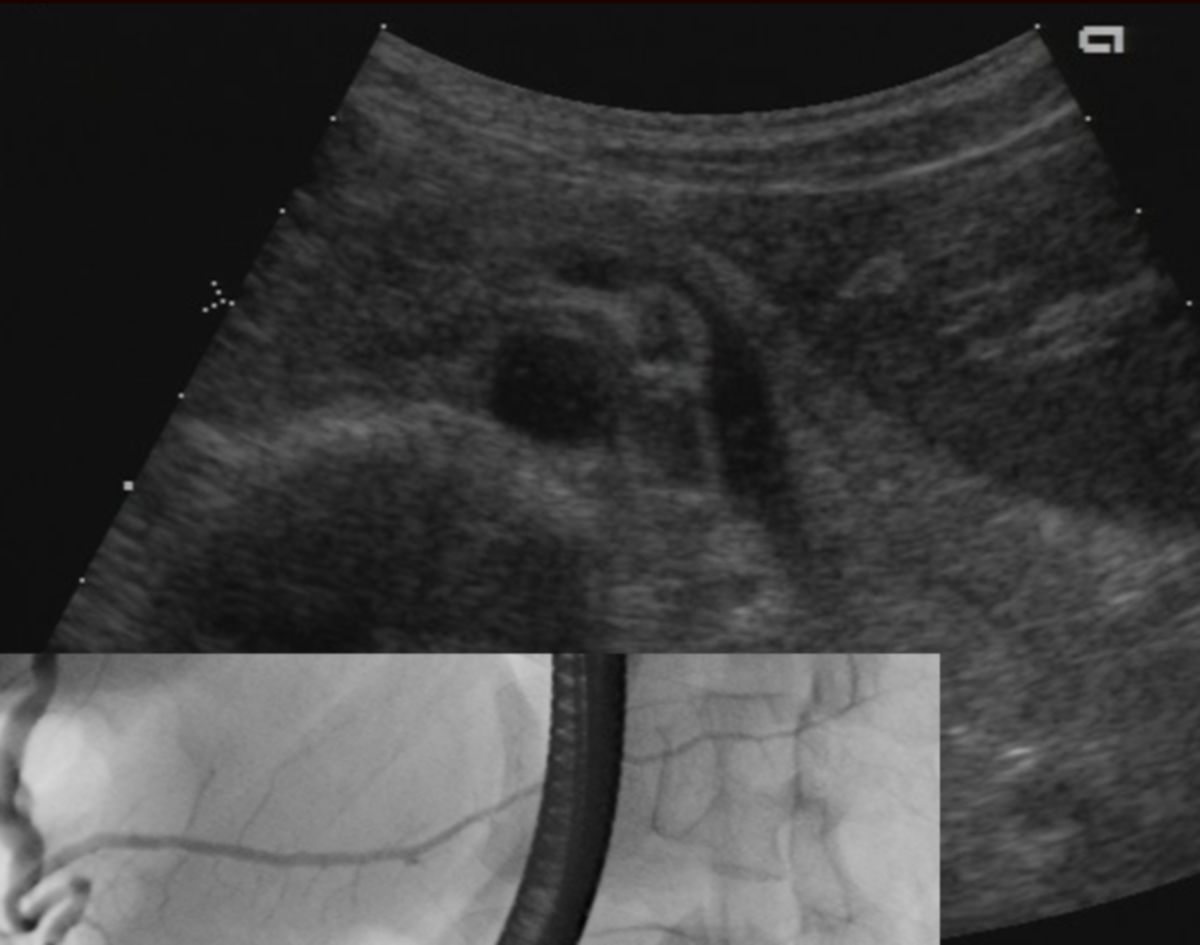

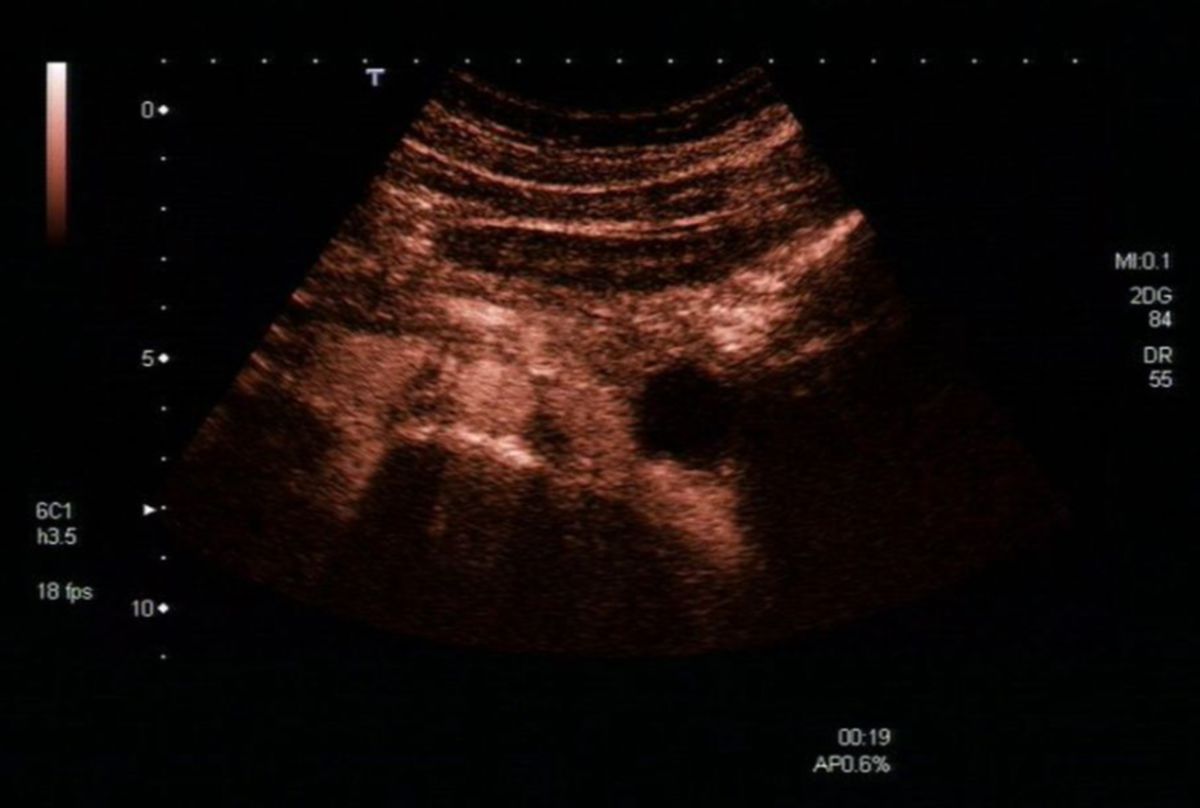

6.2. Examination methods

In addition to taking a detailed medical history, laboratory blood tests measuring the concentrations of amylase, lipase, or elastase are crucial in diagnosing pancreatic diseases. The secretin-pancreozymin test can be used as a functional assessment of the pancreas. Diagnostic imaging techniques such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) also play important roles in evaluating pancreatic conditions.

6.2.1. Surgery

Since the omental foramen is too small to provide access to the pancreas, the omental bursa is opened surgically by cutting the gastrocolic ligament, hepatogastric ligament, and gastrosplenic ligament to allow entry.

In cases of pancreas annulare (a condition where pancreatic tissue encircles the duodenum), the pancreas must not be cut due to its strong blood supply. Instead, the duodenum is divided and rejoined next to the pancreas to avoid compromising the pancreatic tissue.

8. Sources

- ↑ John H. Schaefer: The normal weight of the pancreas in the adult human being: A biometric study Volume32, p. 119-132, Issue2 February 1926

- ↑ Omary MB et al: The pancreatic stellate cell: a star on the rise in pancreatic diseases. In: Journal of Clinical Investigation. Vol. 117, No. 1, June 2007, pp. 50-59, doi:10.1172/JCI30082

9. Literature

- Physiology; Pape, Kurtz, Silbernagl, Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart; 7th edition