Corpus: Heart

1. Definition

The human heart is the central organ of the circulatory system. It is a hollow, muscular structure that works as both a pressure and suction pump, moving about 5 to 6 liters of blood per minute throughout the body. It plays a vital role in the cardiovascular system.

Cardiology is the branch of medicine that focuses on the structure, function, and diseases of the heart. The specialized muscle cells that make up the heart are called cardiac muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes.

2. Anatomy

2.1. Overview

The heart is located behind the sternum (retrosternally) in the middle mediastinum and is almost entirely enclosed by the double-layered pericardium. Most of the heart's mass consists of the heart muscle (myocardium), which is lined internally by the endocardium and covered externally by the epicardium.

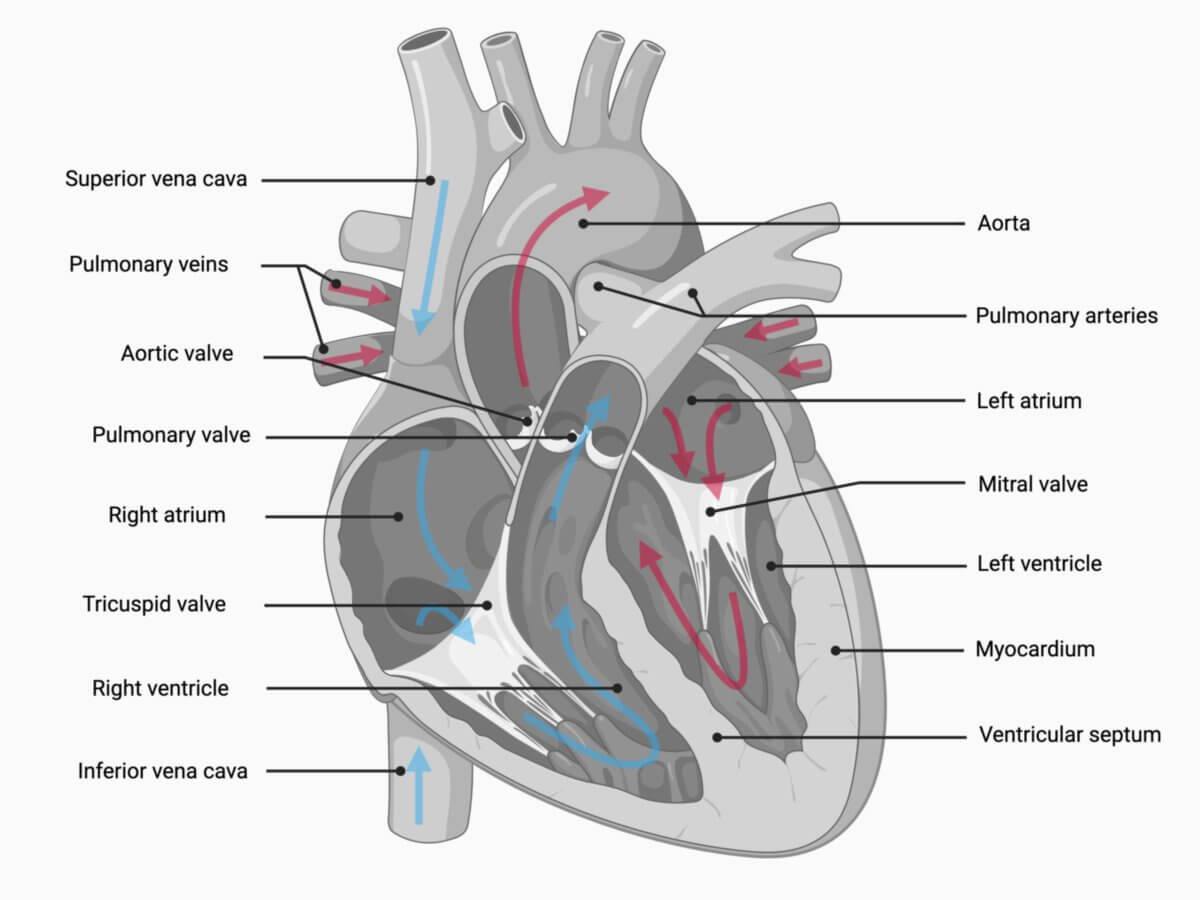

Anatomically, the heart consists of four chambers: two atria and two ventricles. These cardiac chambers are separated by heart valves and connected to either the systemic or pulmonary circulation. The connective tissue that separates the atrial and ventricular myocardium at the level of the valves is known as the cardiac skeleton.

The upper, posterior surface of the heart, where the large blood vessels enter and exit, is referred to as the base of the heart, while the pointed lower end is called the apex of the heart.

The base of the heart is anchored elastically by large blood vessel pedicles (arterial and venous portals) and the bronchopericardial membrane. The freely movable apex of the heart, formed primarily by the ventricles, extends downward and to the left, reaching the midclavicular line at the level of the 5th intercostal space.

The venous system of the heart, known as the venous cross, consists of the superior and inferior vena cava along with the four pulmonary veins. Together, these form the venous portal of the heart. The arterial portal includes the aorta and pulmonary trunk, which spiral around each other at their origins. The right and left coronary arteries, which supply blood to the heart itself, arise from the thickened base of the aorta (aortic bulb).

2.2. Topography

The heart is located within the thoracic cavity in the middle mediastinum, with its outline projected onto the 2nd to 5th ribs. Superiorly, the base of the heart extends about 2 cm beyond the right edge of the sternum, while inferiorly, the apex of the heart lies close to the left midclavicular line. Laterally, the heart is bordered by the pleural layers of the left and right lungs. Posteriorly, the left atrium is in direct contact with the esophagus. Anteriorly, the heart is positioned behind the sternum and the anterior chest wall, with the thymus situated just in front. Inferiorly, the heart rests on the diaphragm, which is fused with the pericardium.

The heart's longitudinal axis is oriented obliquely within the thoracic cavity, running from the upper right (dorsocranial) to the lower left (ventrocaudal). This orientation has an inclination of approximately 45° in the horizontal, sagittal, and frontal planes.

2.3. Dimensions

In adults, the heart measures approximately 12 cm in length, 8 to 9 cm in width at its broadest point, and about 6 cm in depth. Its weight ranges from 280 to 340 grams in males and 230 to 280 grams in females. The heart's mass gradually increases throughout most of a person's life.

2.4. Classification

The heart is divided vertically into right and left halves by septa, and horizontally into two atria and two ventricles by a circular constriction and leaflet valves. This structure creates four distinct chambers:

- Right atrium

- Right ventricle

- Left atrium

- Left ventricle

This internal division is also visible externally. The atria and ventricles are separated by a groove called the coronary sulcus. The anterior interventricular sulcus and posterior interventricular sulcus are grooves between the ventricles, marking the separation of the heart muscle on its external surface.

The atria also feature small, ear-shaped extensions known as auricles or cardiac ears.

2.5. Outer surfaces

The heart has several distinct external surfaces:

- Sternocostal surface: This convex surface faces the sternum and ribs. It is primarily formed by the right ventricle.

- Diaphragmatic surface: This dorsocaudal, flattened surface rests on the diaphragm.

- Pulmonary surfaces: The right and left sides of the heart face the lungs. The left pulmonary surface is formed by the left ventricle, while the right pulmonary surface is formed by the right atrium.

- Posterior surface: This craniodorsal portion of the heart’s posterior side faces the posterior mediastinum and is in contact with the esophagus. It is largely formed by the left atrium.[1]

2.6. Internal surfaces

The inner surface of the heart, lined by the endocardium, is not smooth or featureless. In the ventricles, it is covered with interconnected, rounded muscle ridges known as trabeculae carneae. The papillary muscles, which help control the movement of the leaflet valves, also originate here. These muscles are connected to the valves by thin, tendon-like structures called chordae tendineae, which tighten to ensure proper valve function during contraction

2.7. Blood supply

The heart receives arterial blood through two large coronary arteries: the right coronary artery (RCA) and the left coronary artery (LCA). These arteries form numerous anastomoses with each other; however, these connections are not sufficient to establish a complete collateral circulation. For this reason, they are referred to as functional end arteries. If a branch of a coronary artery is blocked, the area it supplies may experience ischemia. Prolonged ischemia leads to necrosis of the affected heart muscle tissue.

Venous blood is drained from the heart via the coronary veins, including the great cardiac vein, into the coronary sinus.

The coronary arteries are responsible for the heart's own blood supply, referred to as the vasa privata. Approximately 75 % of the venous blood from the heart drains into the coronary sinus, which empties into the right atrium. The remaining 25 % flows directly into the atria and ventricles through the small cardiac veins (Thebesian veins).

For more detailed information, see: coronary arteries and cardiac veins.

2.8. Innervation

The heart's autonomic innervation involves:

- Sympathetic fibers: From the cervical ganglia, known as cardiac nerves (nervi cardiaci).

- Parasympathetic fibers: From the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X).

These fibers form a network called the cardiac plexus at the base of the heart, which regulates cardiac function.

Internally, the heart's activity is controlled by its own cardiac conduction system, which generates and propagates electrical impulses.

2.9. Lymphatic outflow

The heart contains endocardial, myocardial, and epicardial lymphatic vessels. Tiny lymphatic capillaries in the myocardium’s connective tissue (endomysium) merge into small collectors that follow the blood vessels. Larger collectors arise from the epicardial lymphatic vessels and travel along the coronary arteries, reaching the ventral surfaces of the aorta and pulmonary trunk. The main lymphatic trunks include:

- Right cardiac lymphatic trunk (truncus lymphaticus cordis dexter)

- Left cardiac lymphatic trunk (truncus lymphaticus cordis sinister)

These trunks run alongside the great vessels, pass through the edge of the pericardium, and drain into the anterior mediastinal and tracheobronchial lymph nodes via the preaortic and retroaortic lymph nodes.

Additionally, a separate pericardial lymphatic network drains lymph from the pericardium and adjacent mediastinum into the prepericardial lymph nodes and lateral pericardial nodes. The lymph then flows through the mediastinal lymphatic pathways to the parasternal lymph nodes.

3. Histology

The myocardium, like skeletal muscle, is a type of striated muscle. Morphologically, it represents an intermediate structure between smooth muscle and skeletal muscle. The myocardium is composed of individual mononuclear or binuclear cells called cardiomyocytes, which work together to form a functional syncytium. Unlike the nuclei of skeletal muscle cells, which are located at the periphery, the nuclei of cardiomyocytes are positioned centrally.

A distinguishing feature of the myocardium is the presence of intercalated discs between neighboring cardiomyocytes. Under a light microscope, these appear as bright, highly refractive transverse bands that stain more intensely than the surrounding cytoplasm. These intercalated discs serve as specialized cell junctions that mechanically and electrically couple cardiomyocytes, enabling synchronized contraction and efficient bioelectrical coordination.

4. Embryology

4.1. Heart development

The cardiac anlage (also known as the cardiogenic plate) begins forming around the 18th day of embryonic development, near the buccopharyngeal membrane. It arises from two main sources:

- Lateral plate mesoderm: Gives rise to the cardiac tube, blood vessels, epicardium, and pericardium.

- Neural crest cells: Contribute to the formation of the cardiac septum in the outflow tract.

Initially, angioblasts organize into blood islands, which coalesce to form a horseshoe-shaped vascular plexus. Within this plexus, the inner cells differentiate into primitive blood cells, while the peripheral cells become endothelial cells.

The vascular plexus fuses bilaterally to create endocardial tubes. As the embryo undergoes lateral folding, these tubes shift medially and merge to form the unpaired heart tube. Surrounding mesenchymal cells from the visceral mesoderm condense to form the myocardium, while the space between the endocardium (inner lining) and myocardium is filled with cardiac jelly, an extracellular material derived from the mesenchyme.

As the embryo undergoes craniocaudal folding, the heart tube descends (descensus cordis) into the pericardial cavity. This cavity, formed by clefting within the mesoderm, is where the heart tube is temporarily suspended by the dorsal mesoderm. The middle part of the dorsal mesoderm degenerates, creating the transverse pericardial sinus.

The primitive heart tube develops into distinct regions, each contributing to parts of the mature heart:

- Sinus venosus

- Primitive atrium (atrium primitivum)

- Primitive ventricle (ventriculus primitivus)

- Bulbus cordis

- Truncus arteriosus

By day 22, the myocardium begins to exhibit rhythmic contractions.

4.2. Fetal circulation

Two key structures in the fetal heart are essential for fetal circulation:

- Foramen ovale: This opening connects the right and left atria, allowing blood to bypass the lungs, which are not yet functioning in gas exchange. After birth, increased pressure in the left atrium causes the foramen ovale to close. In adults, it remains as a remnant called the fossa ovalis.

- Ductus arteriosus: This is a vascular connection between the aorta and the pulmonary trunk, allowing blood to flow from the pulmonary trunk directly into the descending aorta. It typically closes completely within 10 days after birth.

5. Physiology

The primary function of the heart is to maintain blood circulation, a task referred to as cardiac work or cardiac output. In addition to pumping blood, the heart also plays a role in regulating blood pressure through specialized endocrine cells called myoendocrine cells, especially in the atria. These cells release atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), which helps regulate blood pressure and fluid balance. The heart can also adapt to changes in blood volume. For example:

- Bainbridge reflex: An increase in blood volume leads to a faster heart rate.

- Frank-Starling mechanism: Increased blood volume stretches the heart muscle, enhancing its contractility and improving pumping efficiency.

6. Clinical

6.1. Clinical anatomy

The American Heart Association (AHA) cardiac segmentation system is used to localize clinical findings within the heart.

6.2. Clinical examination

The clinical examination of the heart is essentially based on auscultation of the heart sounds and murmurs and palpation of the pulse.

6.3. Apparative diagnostics

Numerous procedures are available for the examination of the heart. These can be either invasive or non-invasive and include:

- electrocardiogram (ECG)

- chest X-ray

- echocardiography

- cardiac CT

- cardiac MRI

- Left heart catheterisation

- Right heart catheterisation

6.4. Laboratory diagnostics

There are a number of meaningful laboratory parameters for the diagnosis of heart disease. For example:

- Markers for myocardial infarction

- brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) for assessing heart failure

6.5. Important diseases

Diseases of the heart are primarily managed by cardiology. Since the heart and blood vessels work closely together, these conditions are often referred to as cardiovascular diseases. Key conditions include:

- Coronary heart disease (CHD)

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack) or acute coronary syndrome

- Heart failure

- Heart valve disease

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Cardiomyopathies

7. Literature

- Herrmann-Lingen, C.: Depression and coronary heart disease. In: herzmedizin 26 (2009). H.2, S.76-81. Volltext abrufen

8. Weblinks

- 3D animation of the beating heart with lots of information (Hexal)

- DGK Heart Guide (German Society of Cardiology)

- German Society for Thoracic, Cardiac and Vascular Surgery

9. Source

- ↑ Waldeyer et al. Anatomie des Menschen: Textbook and Atlas in One Volume (De Gruyter Studium) (19th totaly rev. ed.), De Gruyter, 2012